Should used-car buyers be wary of dual-clutch transmissions? We investigate some DCT rumours and myths.

Some car buyers may have questions regarding the long-term durability of dual-clutch transmissions (DCTs) - understandably so, given that the repair costs are usually sky-high if they go wrong. In a new car, the warranty and maintenance plans can take care of such issues, but what about buying a used car with a DCT?

A horror story like the ongoing Ford PowerShift saga doesn’t exactly instil a lot of confidence, either, so are these concerns justifiable, and how can an owner mitigate their risks if their vehicle uses this type of gearbox?

A brief history of the DCT

Many enthusiasts believe that it was the VW Group which first brought the dual-clutch transmission to market in 2003, but it story really began in the late 1950s. After the Rootes Group (a now-defunct British car maker) tried and failed to make this clever idea work with the primitive technology at hand back then, Porsche later took up the challenge and began developing the idea 20 years after this first attempt.

They finally took the dual-clutch transmission to motorsport in 1985 (where it won its first championship a year later), but almost two more decades had to pass before Joe or Joan Public could buy one at a VW dealership (and another few years before it arrived in South Africa in the Mk V Golf). Since then, however, this transmission design has proliferated in combustion-engine cars, thanks to its excellent blend of performance, efficiency, and easy driving.

Find your dream Volkswagen Golf right here on CHANGECARS.

Why was the DCT such a big deal?

The road to successful self-shifting transmissions is even longer than the Rootes Group’s pioneering but ill-fated exploration of production DCTs. Drivers have long sought to get away from the faff of changing gears and the tiresome pressing of a clutch pedal, and manufacturers tried for decades to meet this need with pre-selecting gearboxes and automated clutches.

It all eventually came together with the arrival of the torque converter, where the transmission is linked to the engine by a hydraulic power transfer unit instead of a direct clutch coupling. But, while this setup provided very smooth driving characteristics and allowed for compact planetary gearboxes with automatic hydraulically-actuated gear selection to be used, torque converter automatics always carried the penalty of reduced efficiency and lazier performance due to the losses inherent in unlocked torque converters.

The DCT is, at first glance, the perfect mid-point between manual and automatic gearboxes. It uses a direct mechanical drive transfer mechanism, making it just as efficient as a manual because there’s no power-sapping torque converter in the mix, but it can also be made to behave like a normal automatic and take care of pulling away and changing gears. It only needed the control electronics to become compact and affordable enough to become viable, and that’s really what VW and BorgWarner accomplished with their first commercial DSG offering.

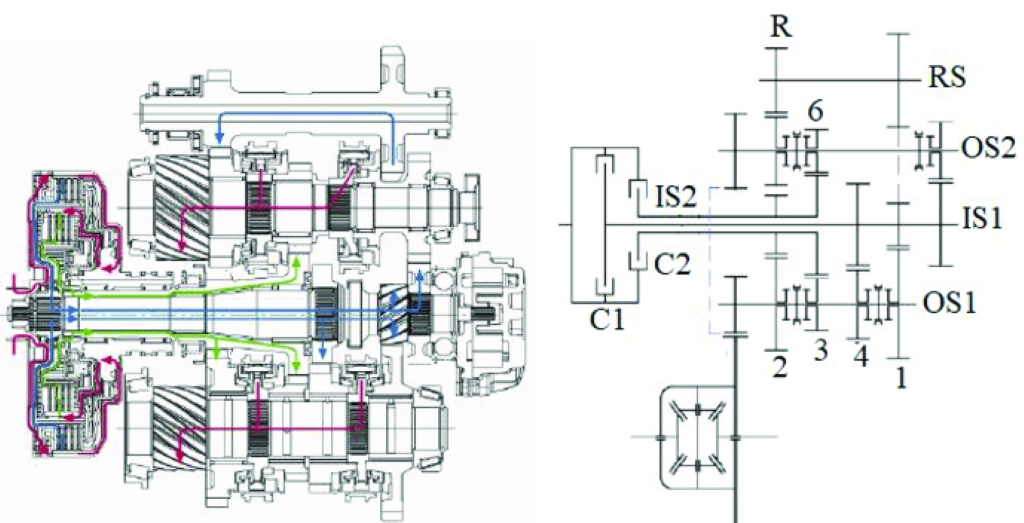

Diagrams courtesy of ResearchGate

How does a DCT work?

The easiest way to visualise a DCT is by seeing it as two manual transmissions in parallel, each with its own friction clutch, operating side-by-side and both driving the same output shaft. The odd-numbered gearsets (1, 3, 5 and sometimes 7) are clustered on one input shaft, and the even-numbered gears (2, 4, 6, and sometimes 8) are clustered on the other input shaft.

By pre-selecting the next ratio while that input shaft’s clutch is disengaged, gear changes can be accomplished simply by releasing the current clutch unit and engaging the next one at the correct moment. There is one important detail to consider, however: Unlike a manual gearbox, the clutches in a DCT are built into the gearbox assembly itself, meaning that a clutch replacement involves disassembling the entire gearbox.

This is a very simple explanation of a very complex piece of engineering, and getting it all to work smoothly requires plenty of back-and-forth communication between the gearbox and engine control systems. That is why the DCT never became successful before the advent of sufficiently powerful electronics, and also explains why no automotive DCT could ever be operated in the same way as a manual gearbox. The DCT is really just a different kind of automatic transmission, theoretically combining the efficiency of a manual with the ease of use of the familiar automatic gearbox.

Driving style differences

Because a DCT’s user interface looks exactly like that of a traditional automatic gearbox, many buyers treat both the same way. “Slip it into ‘D’ and forget about it” about sums up the extent of most drivers’ involvement, and that’s exactly what those buyers prefer.

This approach is fraught with hazards, though. Driving a DCT-equipped vehicle requires a different driving style to the one allowed by a normal automatic, because its hardware operates in a very different manner. But, because many owners don’t realise this, they subject their DCTs to treatment that would have even the beefiest manual gearboxes crying out in agony.

The main issue relates to low-speed driving. Under these conditions, where the built-in slippage of a conventional automatic’s unlocked torque converter would allow for significant differences between the engine- and road speeds in first gear, the direct clutch coupling in a DCT really demands to be either fully engaged or fully released. Anything in between requires slipping the clutch, much as a manual gearbox’s clutch needs to be slipped slightly when pulling away.

Some clutch slip in low-speed, low-torque driving can be absorbed without detrimental effects or significantly reduced clutch life, but sustained slippage will see the clutches overheat and wear prematurely, and soon lead to a transmission rebuild. This DCT problem becomes apparent in heavy traffic and in parking manoeuvres (especially on inclines), where the gearbox is programmed to slip the clutch to emulate the behaviour of a normal automatic, quietly eating its own clutches to provide a smoother driving experience.

How can you make your DCT last longer?

Many a DCT have come to an expensive and premature end due to excessive clutch slip over extended periods, and most of these instances could have been avoided if their drivers only adapted their driving styles according to the requirements for a long DCT service life. Essentially, much of the potential clutch damage can be mitigated if a DCT driver adopts some manual gearbox driving practices rather than treating it like a normal automatic.

The key here is that clutch slip must be kept to a minimum, with the driver committing to either accelerating, cruising or coasting, while reducing instances of low-speed crawling. As long as the clutches are fully engaged, they don’t wear, but if they slip, they wear out much quicker and that repair bill comes ever closer. This is even more pertinent in cars with dry-clutch DCTs, because those tend to overheat and fail in record time when subjected to prolonged slipping since they’re not cooled by the transmission fluid.

Rigorous maintenance is required

Another essential part of prolonging the service life of a DCT lies in its maintenance. Because these gearboxes are subjected to unusual stress factors, proper lubrication with special fluids is required. These fluids have a finite lifespan, and eventually lose their special properties due to repeated heat cycles.

Additionally, some mechanical debris due to normal wear of the clutches and gearsets always finds its way into the transmission fluid, which could end up inside the gearbox’s hydraulic actuators and necessitate a mechatronic unit rebuild as well as a clutch replacement.

This is why servicing requirements for DCTs are very strict, with fluid- and filter changes recommended as early as every 40 000 km. The DCT service interval may vary according to manufacturer, but, because replacing the transmission fluid and filter is much less costly than rebuilding the gearbox, it’s better to rather service any DCT even more frequently than the owner’s manual suggests.

Should you buy a used car with a DCT?

While some DCT-equipped vehicles came with objectively bad gearboxes, specifically the Ford PowerShift ‘DPS6’ and VW Group products with the DQ200 transmission (which are both low-torque, dry-clutch setups with poor reputations), many DCTs have proven to be as durable as most conventional automatic gearboxes. There isn’t any issue with getting a well-engineered DCT to face the monumental challenges posed by a performance car, so normal vehicles shouldn’t have many problems, either.

Mercedes-AMG sends 500 Nm into the 8-speed DCT used in their A45 S, and Audi feeds their 7-speed S-Tronic in the RS3 with just as much torque. Porsche, being the DCT pioneer, also still believes in this technology, and uses an 8-speed unit (called PDK in Porsche-speak) to absorb the 800 Nm on tap in its 911 Turbo S.

Interested in a new or used Audi S3 or RS3? Find your perfect car here on CHANGECARS!

It is however crucial to ensure that a used vehicle’s DCT has been maintained properly before signing on the dotted line. Rather skip those cars with dubious software mods and patchy service records, because you’ll never know what expenses lie in wait around the bend.

Also be sure to test drive any vehicle with a DCT, paying specific attention to erratic or hesitant gear changes while driving, as well as any drivetrain shudders or noises when pulling away. Those are fairly definite indications that all is not well in the transmission department, and you’d be better off checking out another car instead. But, if you find a used car with moderate mileage and a sound DCT, just drive it with due care for the limitation of its transmission type and keep up with its servicing, and it should serve you at least as well as any other gearbox.

Martin Pretorius

- Proudly CHANGECARS